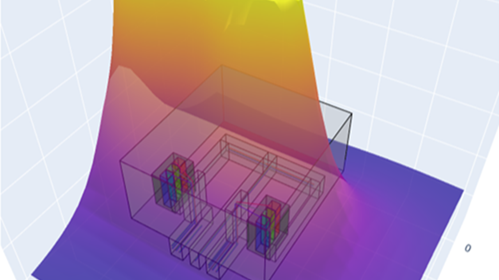

EMC – Electromagnetic Field Maps

EMC field mapping of a Transformer Substation

What is an electromagnetic‑field map and what is it used for?

In the world of electrical infrastructure — whether in transformer stations, medium‑voltage (MV) lines, substations or other grid assets — it is increasingly important to understand how electric and magnetic fields (EMF) behave in the surrounding space. An electromagnetic‑field map (sometimes also called an EMF map, E‑field/H‑field distribution map, or simply a “field map”) is a spatial representation of how these fields are distributed in 3D‑space around the infrastructure.

Such maps are critical for several reasons:

To assess public exposure: we need to know how high the fields are in zones accessible by people (homes, schools, hospitals, offices) and whether they comply with applicable regulatory limits.

To verify compliance with national or regional legislation. For example in Spain, Real Decreto 1066/2001 sets a public‑exposure limit of 100 µT (microteslas) for magnetic fields at 50 Hz.

To support planning, design and permitting: Many electrical‑infrastructure projects (new substations, MV lines, expansions) require either environmental permitting or urban‑planning approval. A field map helps justify siting, shielding or mitigation measures.

To detect sensitive locations or critical areas: It helps identify dwellings, schools or other locations where the field exceeds “normal background” levels or approaches regulatory thresholds.

To guide corrective or mitigative design: By visualising the field distribution, engineers can design measures (shielding, spacing, alternate conductor arrangements, rerouting) to reduce exposure in critical zones.

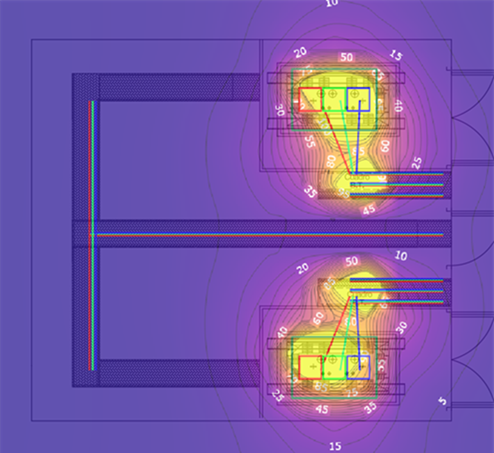

EMC Field mapping – Top View

How are the fields calculated?

Creating an EMF map relies on standard electromagnetic theory, validated measurement and modelling practices, and recognised standards.

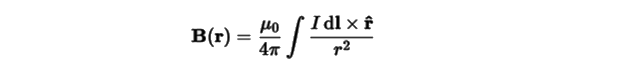

1. Theoretical basis

For magnetic fields generated by power systems (typically at 50 Hz or 60 Hz), one of the foundational laws is the Biot–Savart Law, which allows the magnetic induction B to be estimated from current intensity I and the geometry (position, length and orientation) of conductors.

Biot-Savart Law

Where dl is the elementary length vector of the conductor, r is the vector from the conductor segment to the point of interest, and μ₀ is the vacuum permeability.

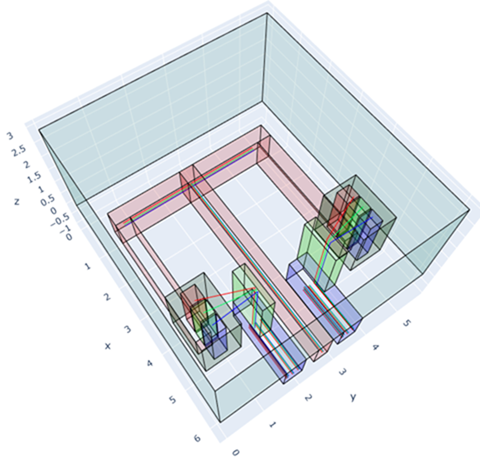

While the Biot–Savart Law gives an analytical foundation, practical modelling of real infrastructures (busbars, switchgear, trenches, shield wires, grounded conductors, laminations) typically uses numerical or semi‑analytical methods (finite‑element method, boundary‑element method, analytical approximations) to compute field distributions.

2. Modelling inputs

To build a realistic EMF map, the following inputs are typically required:

3D configuration of the installation: Is the line overhead or underground? Are the conductors arranged in spaced phases or tightly bundled? Is the substation indoor or outdoor? Are busbars compact or widely spaced?

Load current and service voltage: The current (and its harmonics) flowing through conductors is a primary driver of the magnetic field.

Geometry, spacing and arrangement of conductors/busbars: Phase separation, conductor height above ground, conductor orientation, presence of return conductors, shielding wires, ground reference structures all matter.

Distance to dwellings or accessible zones: Because field intensity falls off with distance (approximately ~1/r for long straight conductors), the position of interest relative to the source is critical.

Transformers and switchgear: Transformers may include return paths, shielding, core saturation effects; switchgear can include bus ducts, large currents; these affect field patterns.

Validation/measurement data: Modelling is typically validated (or calibrated) with actual measurements in the field.

3. Reference standards

Several standards define procedures, instrumentation, and measurement protocols in this domain:

Demonstrate compliance: For example, in Spain, Royal Decree 1066/2001 limits the public exposure to 100 µT at 50 Hz for magnetic fields. A map demonstrating field levels around a new installation helps show compliance (or identify non-compliance)..

Permit or planning justification: When projects are subject to environmental permitting, urban planning or public consultation (“¿por qué aquí y no en otro sitio?”), an EMF map gives credible data showing that field levels near sensitive receptors (homes, schools, hospitals) are acceptable or that mitigation is feasible.

Identify critical or occupied areas: The map helps highlight where field levels are significantly higher (near conductors, busbars, transmission lines) and may impact occupancy or access. This allows engineers to adjust design (increase spacing, move conductors, add shielding).

Design corrective measures: If field levels exceed acceptable limits or are uncomfortable, the map helps engineer mitigation: e.g., relocating conductors, adding ferromagnetic shields, rerouting cables underground, arranging busbars in inversion, or adding screening to transformers.

Communicate with stakeholders: Visual field maps are a powerful tool in stakeholder communication: regulators, municipalities, neighbourhood associations. They transform abstract numbers into spatially understandable graphics.

Model in Software CRMagPlus

Electromagnetic engineering for safe infrastructures compatible with their surroundings

As electrical infrastructures expand and integrate more closely with urban or semi-urban environments (renewables, smart grids, HV/MV upgrades), it is no longer enough to assume that field levels “just fall off with distance”. High currents (e.g., from wind-farm collection systems, MV feeders), compact substations, and undergrounding increase complexity.

By integrating rigorous modelling (in-line with standards such as IEC 62110, IEC 61786) and measurement verification, engineers can ensure that installations are technically safe, regulation-compliant and socially acceptable.

In short: an EMF map is not just a technical deliverable—it is a bridge between electrical-engineering design and the environment / public exposure domain.

EOHM© 2025